Insiders know stuff they don't want us outsiders ever to.

"These policies are insane, if one assumes a minimum of public spiritedness. They have not worked. They will not work.

"But they do work in the social sense: They create successful lives for the people who devise and implement them. They are rewarded with money and social approval, they receive feedback which screams, 'Continue!' "

-- Ian Welsh, in his post yesterday,

"The Political Consequences of Mental Models"

"The Political Consequences of Mental Models"

by Ken

In the above quote pulled out of Ian Welsh's post yesterday, I realize I've left out which policies "these policies" refers to. Really, it almost doesn't matter. It should be clear that the reference is to policies promulgated by people in a position to set policy, and the model Ian proposes works for pretty much any policies such people are likely to promote.

Still, for the record, here are some of the instances Ian had just cited:

• "the repeated use of force in situations where force has failed to work over and over again."

• "the inability to tolerate democratic governments of opposing ideologies despite the fact that destroying them, after a period of autocracy, generally leads to worse outcomes than simply working with them. (See Iran for a textbook case.)"

• "the belief that the US needs to run the world in tedious detail, that regular coups, invasions, garrisons, and so on are necessary -- along with the endless, sovereignty-reducing treaties described in 'free trade deals.' "

These are policy choices dictated by conditioning, beliefs that people believe because they've been conditioned to, usually according to mental models developed in their minds through processes that have little -- if anything -- to do with actual thought. Ian had begun by pondering the question of whether Western leaders have deliberately destabilized the Middle East. Which landed him in an age-old conundrum:

Q. "Stupid or evil?"

A. "Both."

DICK CHENEY: MAKING THE WORLD A BETTER PLACE

By way of illustration in this post, called "The Political Consequences of Mental Models," Ian offered this case:

I know someone who worked with Cheney and believes that Cheney honestly thought that removing Saddam would make the world a better place. Also (and the person I know is a smart, capable person) that Cheney was very smart.Which prompted some thoughts on the human "thought" process (and here I would stress that "thought" is being used in its broadest possible sense, referring to not necessarily much more than "activity in the brain").

But smart in IQ terms (which Cheney probably was) isn’t the same as having a sane mental map of the world. Being brilliant means being able to be brilliantly wrong and holding to it no matter what. Genius can rationalize anything.

Human thought is mostly an unconscious and uncontrolled process. What comes up is what went in, filtered through conditioning. We are so conditioned and the inputs are so out of our control during most of our lives (and certainly during our childhood) that our actual, operational margin of free will is far smaller than most believe."The science of conditioning," Ian wrote, "was strong from the late 19th century through to the 60s," but "has faded out of the intellectual limelight." However, "viewed through the lens of conditioning, much that makes no sense makes perfect sense."

We interpret what we know through the mental (and emotional) models we already have. Thoughts are weighted with emotion, recognized and unrecognized, connotations far more than denotations.

Machiavelli made the observation that people don’t change, they instead react to situations with the same character and tone of action even when a different action would work better.

This doesn’t mean one cannot undergo ideological changes, it means character changes only very slowly, and that we have virtually no conscious ability to change our thinking, actions, or characters on the fly.

This is true for both the brilliant and the stupid, though the tenor of challenges for both is different.

Ian offered a classic example: the "insider" perspective vs. the "outsider" one:

Over fifteen years ago Stirling Newberry told me, “Insiders understand possibility, outsiders understand consequences”."Conditioning," Ian wrote, "extends well beyond observable behavior and into thought, and the structure of knowledge."

Insiders are rewarded for acting in accordance with elite consensus, and very little else.

Outsiders, not being part of that personal risk/reward cycle are able to say, “Yeah, that’s not going to work”.

They are both right and wrong.

Intellectual structures are felt, and each node and connection has emotional freight. This is true even in the purer sciences, and it is frighteningly true in anything related to how we interact with other humans and what our self-image is.

It is in this sense that the disinterested, the outsider, those who receive few rewards for acquiescence, are virtually always superior in understanding to those within the system. Outsiders may not understand what it “feels” like, but the outsider understands what the consequences are.

THE MYSTIQUE OF "INSIDE KNOWLEDGE"

Those of us who lived through the Vietnam war became accustomed to being told that opposition to it was based on inadequate knowledge, that the people who were making our policy, who were prosecuting the war, had all kinds of knowledge about the situation that we didn't, and they therefore had to be deferred to. Naturally they couldn't share this inside knowledge with us, because it was, you know, inside knowledge. It was secret, and therefore knowable only to insiders wise enough and security-cleared enough to possess such knowledge.

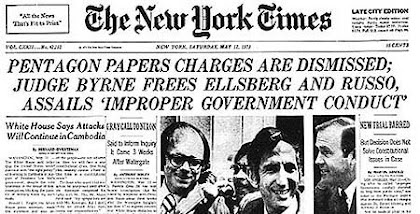

Eventually, of course, and still totally unbeknownst to us benighted outsiders, as inside an insider as Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, who had been as responsible as anyone for enmeshing us in the conflict, began to have doubts about the quality of that inside knowledge, which led to the Pentagon Papers, which still had to remain secret -- until they weren't, thanks to Daniel Ellsberg, with assists from the highest decision-making levels of the New York Times and the Washington Post, and others as well, not least the U.S. Supreme Court.

For his efforts Ellsberg was charged with assorted acts of espionage, theft, and conspiracy, which Wikipedia reminds us "carr[ied] a total maximum sentence of 115 years."

Not many people nowadays think of Ellsberg as a traitor, which is why the insiders who rose in righteous wrath against Edward Snowden had to go to such pains to distinguish Snowden's leaks from Ellsberg's. Unfortunately for them, Snowden's revelations turned out to be a gift that kept on revealing, and the more that was revealed, the more foolish the people who were denouncing him as a traitor came to look. This was all "inside knowledge" being revealed, and to the people who had previously had exclusive access to it, it was awfully important that it remain secret.

And it's very likely that some of them, at least, believed as sincerely as Ian's acquaintance insists Dick Cheney did that they were doing a wise and patriotic thing, helping make the world a better place, by both acting on and suppressing all that information. It's very likely too that many of them were confirmed in their beliefs by just the sort of conditioned "mental models" Ian was writing about yesterday.

Again, as Ian put it, "the disinterested, the outsider, those who receive few rewards for acquiescence, are virtually always superior in understanding to those within the system. Outsiders may not understand what it 'feels' like, but the outsider understands what the consequences are." And he concluded:

This is true far beyond politics, but it is in politics where the unexamined life, the unexamined belief structure, and the unexamined conditioning, are amplified by long levers to brutalize the world.

The last thing I. F. Stone wanted to be was an insider.

#